AI in Education: Bans, Policies, and the Shift Toward 'AI-Allowed' Classrooms

Educational institutions are abandoning ineffective AI bans in favor of structured policies, redesigned assessments, and AI literacy curricula. Schools shift toward process-based evaluation, explicit usage guidelines, and teaching critical AI skills. Detection tools show significant limitations. The transition from prohibition to integration is uneven but reflects growing recognition that AI literacy is now essential.

10/30/20234 min read

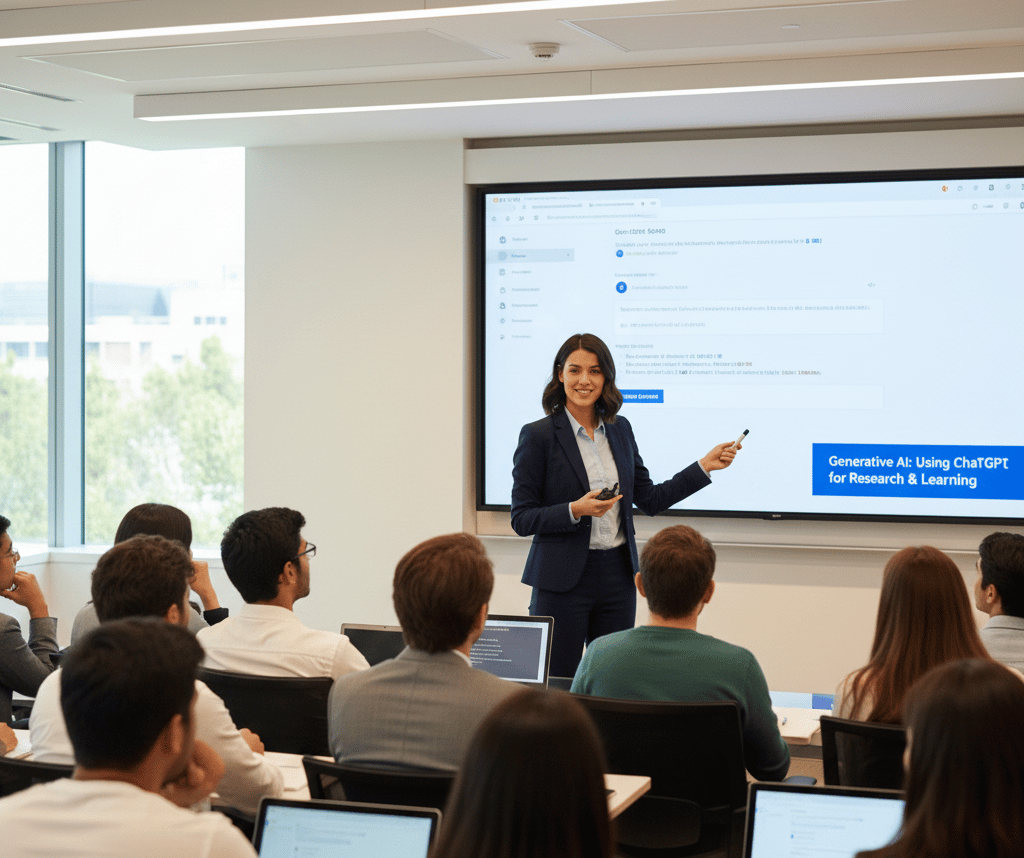

When ChatGPT launched last November, the education sector's initial response bordered on panic. School districts rushed to block the service on their networks. Universities issued stern warnings about academic integrity. Teachers worried that essay assignments had become instantly obsolete. The consensus seemed clear: AI was a cheating tool that needed to be banned.

Ten months later, the conversation has fundamentally shifted. Forward-thinking educators now recognize that banning AI is both impractical and counterproductive—akin to banning calculators or the internet itself. The focus has moved from prohibition to integration, from panic to pedagogy. But this transition is messy, uneven, and raising questions educators are still struggling to answer.

The Failed Experiment with Bans

The initial wave of AI bans proved ineffective almost immediately. Students could access ChatGPT on personal devices, through VPNs, or via dozens of alternative interfaces. The technology was simply too accessible to meaningfully restrict.

More fundamentally, educators began questioning whether bans made pedagogical sense. Students entering the workforce will encounter AI tools routinely. Preventing them from learning to use these technologies responsibly seemed increasingly short-sighted—like teaching writing without allowing word processors.

Several high-profile educators publicly reversed their positions. Ethan Mollick at Wharton went from considering bans to making AI tools mandatory in his courses. His argument resonated: if AI will be ubiquitous in professional contexts, education should teach students to use it effectively and ethically, not pretend it doesn't exist.

By spring 2023, the conversation had shifted from "how do we block this" to "how do we incorporate this responsibly."

The Emergence of AI Usage Policies

Universities and school districts have begun crafting explicit AI usage policies, though approaches vary dramatically. Some institutions require students to disclose any AI assistance on assignments. Others permit AI for certain stages of work—brainstorming, outlining, research—but not for final drafts. Still others adopt assignment-specific policies, allowing AI for some projects while prohibiting it for others.

Harvard's policy exemplifies the nuanced approach many institutions are adopting: AI tools are permitted for research and idea generation but must be cited like any other source. Students must understand and be able to explain any work they submit, whether AI-assisted or not. The policy emphasizes that AI should enhance rather than replace learning.

These policies attempt to strike a balance between acknowledging AI's inevitability and maintaining academic integrity. But implementation proves challenging. What constitutes appropriate disclosure? How much AI assistance transforms "your work" into something else? These questions lack clear answers, creating gray areas that both students and faculty navigate uncertainly.

Redesigning Assessment

The more fundamental response involves rethinking assessment itself. If AI can generate competent essays in seconds, perhaps essays were never the best way to evaluate learning in the first place.

Educators are experimenting with alternatives: oral examinations, in-class writing, project-based assessment with documented process work, and assignments requiring personal reflection AI cannot replicate. The shift mirrors how mathematics education evolved after calculators became ubiquitous—less emphasis on computational mechanics, more on conceptual understanding and application.

Some professors now design assignments that explicitly incorporate AI, asking students to critique AI-generated content, improve AI outputs, or use AI as a collaborative tool while documenting their process. These approaches treat AI literacy as a learning objective rather than a threat.

Process-focused assessment also gains traction. Instead of evaluating only final products, educators assess research notes, draft iterations, and revision processes—artifacts harder to fake with AI and more revealing of actual learning.

The AI Literacy Imperative

Perhaps the most important shift is treating AI literacy as a core educational competency. Just as schools teach information literacy—evaluating sources, distinguishing reliable information from misinformation—they increasingly recognize the need to teach AI literacy.

This includes understanding AI capabilities and limitations, recognizing when AI outputs are unreliable or biased, using AI as a tool rather than a replacement for thinking, and developing prompting skills to work effectively with AI systems.

Some institutions have created dedicated AI literacy curricula. Others integrate it across subjects—science classes examining how AI models work, humanities courses analyzing AI-generated text critically, social studies exploring AI's societal implications.

The goal isn't making students AI experts but ensuring they approach these tools with appropriate sophistication: recognizing both utility and risks, understanding what AI can and cannot do, and developing judgment about when and how to use it.

Detection Tools and Their Limitations

Meanwhile, AI detection tools like Turnitin's AI detector and GPTZero have emerged, promising to identify AI-generated text. Educational institutions initially embraced these tools as enforcement mechanisms, but enthusiasm has cooled as limitations became apparent.

Detection accuracy remains problematic. False positives flag legitimate student work, particularly from non-native English speakers whose writing patterns may resemble AI output. False negatives miss AI-generated content that students have lightly edited. The arms race between detection and evasion continues, with students learning to modify AI output to evade detection while detectors chase improved accuracy.

More philosophically, over-reliance on detection tools risks creating adversarial relationships between students and educators. The focus becomes catching cheaters rather than supporting learning. Some educators argue that if we're primarily concerned with detecting AI use, we've designed the wrong assignments.

Detection tools may have a role—flagging work for further review, identifying patterns suggesting systematic misuse—but they're increasingly seen as insufficient solutions to a pedagogical challenge requiring pedagogical responses.

The Uneven Transition

The shift from bans to integration proceeds unevenly. Well-resourced institutions with faculty interested in educational technology are developing sophisticated approaches. Under-resourced schools and overworked teachers often lack time or support to rethink pedagogy fundamentally. The result is inconsistent policies creating confusion for students navigating different expectations across classes.

The transition also reveals deeper questions about education's purpose. If AI can handle many tasks we've traditionally taught, what should education focus on instead? Critical thinking and creativity emerge as common answers, but these are harder to teach and assess than the mechanical skills AI now replicates easily.

What's clear is that the "AI-allowed" classroom isn't simply the old classroom with AI added. It's a reimagining of what education looks like when certain capabilities become universally available. We're still in the early stages of this reimagining, experimenting with policies and pedagogies while the technology continues evolving beneath our feet.